Zoos

Zoos often inspire strong emotions. Many humans love them, but others consider them immoral. And zoos themselves vary tremendously. Some are large entertainment complexes, while others are reserves dedicated to providing shelter to animals who can't survive on their own. Very few of my closest relatives (the canadensis branch of the Grus family) end up in zoos. We're too common to either attract big crowds or need protection. But many of my cousins are less fortunate. And I have to say, for them it's a mixed bag.

On the One Hand

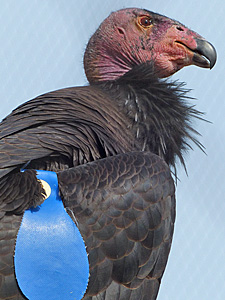

Zoos are a great resource for humans. They give parents the opportunity to teach their children about animals they might not see otherwise. I'm sure the boy on the left would never have gotten this close to California condors (Gymnogyps californianus) if he hadn't been able to visit them at the San Diego Zoo. These majestic scavengers nearly went extinct a few years back, and there are still only a few hundred living in the wild. Zoos may be safer too. Animals typically live longer in zoos than they do in the wild. And if the glass between that polar bear (Ursus maritmus) and the humans were to disappear, you can bet the humans would be scrambling to escape!

When humans have the chance to see real animals, rather than simply watching them on television, they often appreciate them more. In theory, they may be motivated to act and protect them.

On the Other Hand

I can't help it, my heart just breaks when I see the expressions on some zoo animals' faces. Many animals are nomadic in their natural environment; they're constantly exploring and on the prowl. Some animals, like elephants have complex social behavior and need to interact in large groups. The environment in many zoos prohibits these deeply ingrained instincts.

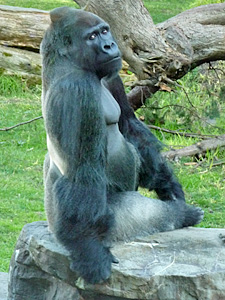

The Grus family is famous for its strong pair bonds. Most of us mate for life. We just aren't meant to live alone, but this red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis) has had to adapt to a solitary lifestyle. Other animals, like this gorilla (Gorilla gorilla) dislike direct eye contact. For them, a endless stream of staring visitors is a constant challenge.

Zoos As Entertainment

In theory, zoos can teach humans to appreciate nature. But sometimes I wonder if they have the chance to learn when they are so distracted by the entertainment options many zoos provide. The San Diego Zoo Safari Park is world renowned for its large, naturalistic enclosures and its preservation of endangered species. But recently it has become equally known for a dizzying array of entertainment options. An interactive animated zebra chats about animals with children near the entrance of the zoo, while older kids can ride a zip line across an enclosure. Cheetah runs, balloon rides and safaris through the enclosure also attract visitors who would be bored by merely watching animals.

Uh Oh, We Have Yet Another Hand!

Zoos may also be an important haven where species can breed safely until humans figure out how to play nicely with others. Some species, like the Southern White Rhinos are threatened by poachers in the wild. The San Diego Zoo Safari Park, where baby Kayode (pictured above) was born in February 2013, has a very successful breeding program for white rhinos. In some cases, these captive breeding programs are absolutely critical. The San Diego Zoo also participated in the captive breeding program that is credited for saving the California Condor (pictured above) from extinction.

Who Decides Which Animals Can Breed?

In the wild, survival skills and luck determine which animals get to breed. But once humans are involved, everything becomes much more complicated. For millennia, humans have bred animals to foster traits that made them better helpers. Trainability, thick wool, lots of milk . . . you get the idea. These things are great for the humans, but they often have little to do with the success of the species. This may not be a huge deal when populations are huge, but it becomes a problem when the animal is endangered. The gene pool is so small that important survival traits may be lost forever.

Tigers illustrate this issue very well. Humans are very fond of white tigers, like this one at the Secret Garden and Dolphin Habitat in Las Vegas. They are beautiful animals, even a Grus can see that!. The problem is that white tigers have two rare recessive genes, and they are essentially the result of excessive inbreeding. This means white tigers are more vulnerable to health issues like weak kidneys, club feet, and problems processing visual stimuli. In 2011 the Association of Zoos and Aquariums banned its members from breeding white tigers. All tigers are endangered, and member zoos participate in careful selection of animals to preserve the gene pool that remains. For example, the Sumatran cub born in the San Francisco Zoo early in 2013 was conceived when the New Orleans Zoo sent their male tiger Larry to mate with San Francisco's Leanne. This approach is very important because fewer than 400 Sumatran tigers remain in the wild.

But white tigers remain very popular with zoo visitors, and despite these concerns some zoos keep breeding them. Early in 2013, the Tobu Zoo introduced four baby white tigers to the public. If you want to learn more about the white tiger controversy, check out this article in Slate.